Television shows are a blessing and a curse. A chance to escape, a chance for education, a chance for adventure. While people tend to watch television for different reasons, the characters bring them back to the same television shows. If you don’t like the characters of a show, you aren’t likely to give that program a second chance. Last week, I discussed three heroines whose characters sparked imagination and became favorites of viewers. As writers, learning from television characters can help with our own writing. Lucy Ricardo had goals and wanted stardom, Mary Richards had heart and formed a family of her friends and co-workers around her, and Jessica Fletcher found more conflict and more dead bodies than any of us would ever want to encounter but we loved watching anyway. Today, I’m going to delve into secondary characters, three sidekicks who writers can learn from in how the complement or create a foil for the main character.

Dan Fielding (the womanizing foil). In the eighties, I loved being able to stay up past my bedtime and watch Night Court. Yes, Judge Harry Stone was a great main character with magic tricks up his sleeve, Mel Torme on his record player, and wise decisions flowing from the bench. However, Dan Fielding was the reason I kept watching. A perfect foil for the optimistic prosecutor Christine and for the magician judge, Dan Fielding had a pick-up line on his lips and a swagger on his step. A great deal of Dan Fielding’s character is owed to the acting skills of John Larroquette, for it would have been easy to play Dan Fielding as a pure womanizer who didn’t care about anything or anyone besides himself. Yet underneath those smooth lines and leering looks, there was something about Dan that compelled you to keep watching, compelled you to see past those lines and hope his cynicism was just that – a foil to the other characters and a mask to the world. And the finale proved it. For when the gang split up, Dan himself had the biggest surprise up his sleeve. He was following his heart and going after Christine. Her rose glasses and optimism struck a chord in his womanizing heart, and he didn’t want to let her out of his life. The romantic in me who thought all those years Christine and Harry should get together was much more satisfied with this. The foil and contrast of the prosecutor and defense attorney and judge trio kept the show going and kept me tuning in. What could have been a stereotypical character was transformed into a breathing person.

Niles Crane (the stuffy relative). I still remember when Cheers was about to pour its last drink and go off the air. I read an article that said there was going to be a spinoff. I waited with anticipation about which supporting character was going to get his or her show. Would I get to meet all of Carla’s crazy relatives? Would I at last see the elusive Vera? Would Woody leave the bar? None of the above. The spinoff character was going to be my least favorite Cheers character, Frasier Crane. I was hesitant about tuning into the first show. While Frasier had been the center of my all-time favorite Cheers episode (the one where the incomparable Emma Thompson played Frasier’s ex-wife, Nanny Gee), I wasn’t sure if I’d like the new show. Then I watched the first episode and fell in love with Martin, Roz, Daphne, Eddie, and Niles. The producers had created an ensemble cast for the ages. Writers can learn something from each of these characters: how a physical handicap didn’t stop Martin, how a romantic spirit led Daphne to keep looking for love, how to be a strong woman in a male-dominated workplace like Roz. Yet the character who could have been a stuffy relative and nothing more was fleshed out and became likable anyway. Underneath his pretentious mannerisms, Niles longs for love. He’s trapped in a loveless marriage with a toothpick of a wife, but he doesn’t stop yearning for a caring relationship, both with his family and with the woman of his dreams. And by the end of the series, Niles has a son of his own with the woman of his dreams. Layering your supporting characters and making sure they go beyond a stereotype can enrich your writing.

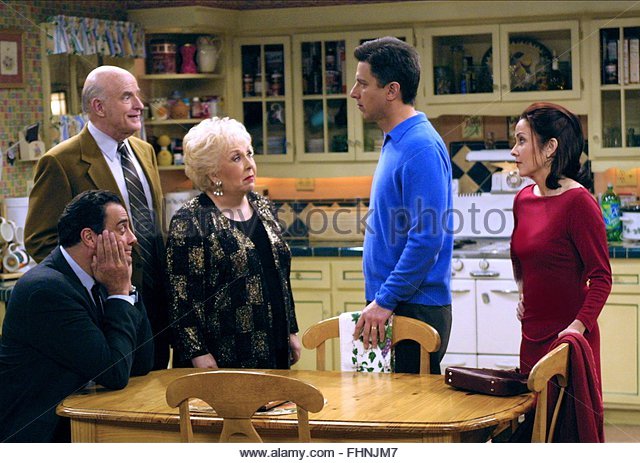

Marie Barone (the meddling mother). Just thinking about Doris Roberts’ portrayal of the meddling Marie brings a smile to my face. The writers didn’t hold back punches with Marie. It was clear she played favorites. It was clear she had opinions of her own about how Ray’s wife should put him on a pedestal. And it was clear she had aspirations of her own when she tried her hand at sculpture. Had the writers just stopped there, Marie would have been the stereotypical mother/mother-in-law character, but fortunately they layered her character with such richness that Doris Roberts sunk her teeth in the role and made her very memorable. How did they layer her character and go beyond the stereotype? They latched onto everyday topics and magnified the humor. In the pilot, Ray tells Marie and Frank he bought them a gift: he enrolled them in a “fruit-of-the-month” offer. Marie and Frank replied they didn’t need it and what became a seemingly minor, run-of-the-mill topic was magnified for laughs. The writers did the same thing for canisters, salmon, and sculptures.

By layering your supporting characters and going beyond stereotypes, you can perk up your writing and make those supporting characters all the memorable. Who are some of your favorite television supporting characters?